The UK’s Digital Economy Bill – failure of an Act

It seems to be a cross-party consensus that anything called a “Digital Economy” Bill will demonstrate how out of touch with digital the authors of Government policy can be. Especially when they have an inability to say not to special interests making a narrow argument.

The current attempt tries to enhance the digital economy with adult content filtering, and then censorship, as a “digital” fix to a social problem of people getting enjoyment from looking at porn. Good luck with that, (although it’s one way for Cabinet Office to get 25 million accounts on Verify).

In the 8 months since the Digital Economy Bill was introduced, the digital world has moved on – treating broken policy intent as damage and simply engineering around it. The Bill received Royal Assent yesterday and is now and Act.

For example, the Act introduces mandatory blocking of websites which don’t implement restrictions on access. That block limits access to a domain name (so your browser can’t work out how to show you what’s on www.ParliamentPorn.uk).

Coincidentally, also yesterday, Ethereum announced the launch of their distributed ledger implementation of DNS, to go from a human readable web address to the content/IP address using the data on the ledger (or at least, bits of it), rather than asking your ISP – who is now required by law to lie to you in the UK, and already routinely would in other countries overseas.

The Act therefore incentivises the use of censorship resistant technologies by those who are most likely to have interest in looking at prohibited content… At least UK teenagers will be more engaged in the digital economy… The Bill assumed that people would use credit cards to assert their identity – because nothing could possibly go wrong with that.

Elsewhere in Ethereum

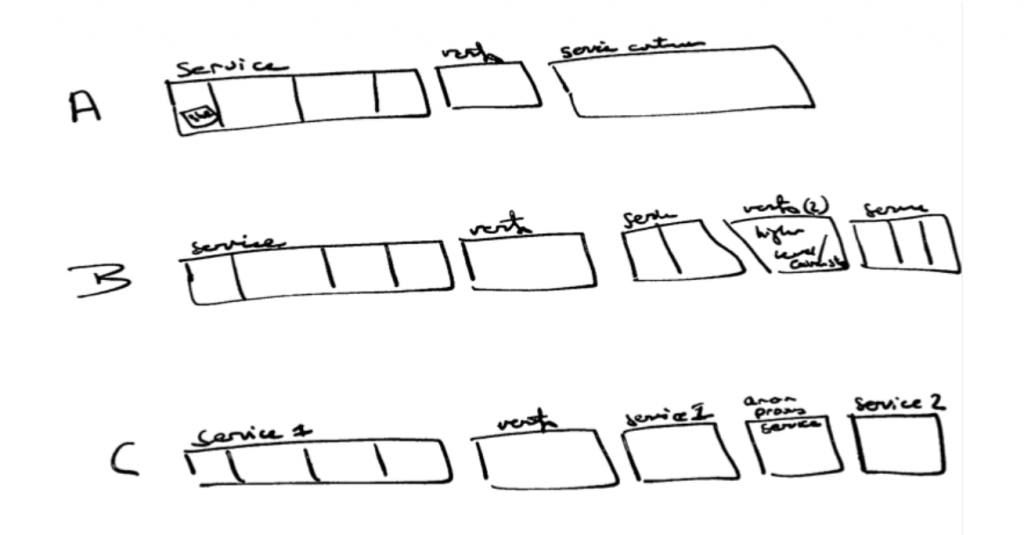

With the ethereum browser plugin giving cryptography, services, and payments, there wouldn’t be an “hard to explain” entries in your credit card history, just another single use address amongst many others, and fully protected from the state snoopers.

Ethereum contains its own currency with micropayments built in (it is the number 2 cryptocurrency behind bitcoin), and is now finalising the design of zero-knowledge proofs – so you can pay someone money, with the sender, recipient, and amount all able to be fully anonymous (which is a higher level than bitcoin, which is pseudonymous).

The systemic incentives in many ways are obvious – using internet agreements, it’s already been shown that a set of creators and contributors to a project can agree to a contract that automatically shares the proceeds in a pre-agreed and privacy preserving way – the “fair trade music industry”. Whether this project gets used or not is up to the world, but it’s possible, and possibility is what a digital economy can produce.

As a side effect of something else, the technically possible has already undermined the Digital Economy Act’s social intent.

A viewer can access something they want to, that otherwise they couldn’t, in a manner that is fully privacy preserving, and also ensure producers can get paid. You can get a trial app for your phone here (which also does secure comms using Signal based on your wallet address rather than email/phone number).

That is what a digital economy should enable, and indeed it does as a side effect… It’d just be nice if one day they did it deliberately…

Disclosure: in my day job, I was looking at (only) Part 5 of the Digital Economy Bill, which is also broken. The above is just me, just for fun.

Ps – the use of ether addresses as Signal endpoints is a rather genius idea, to build on top anything else. Although this story isn’t entirely new.

Disruptive Proactivity

Disruptive Proactivity